Gallery exhibition

more about

Andrzej Wróblewski was born in Vilnius, Lithuania in 1927 and died in 1957 on an excursion in the High Tatras. Within little more than ten years, he developed an aesthetic and symbolic painterly idiom all his own as a means of investigating corporality and ephemerality in his works. His oeuvre is characterized by a gradual transition from abstract to figurative painting.

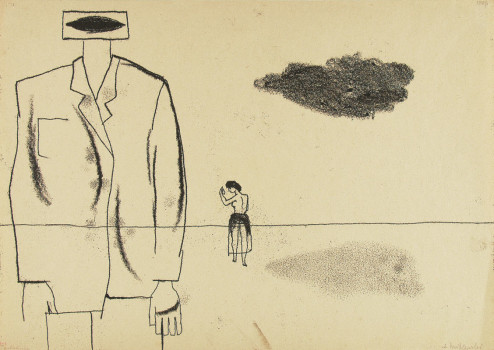

The title of the show at the Galerie Isabella Czarnowska is a reference to a book by the same name – Barbarian in the Garden – containing essays written by the Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert after his first travels to the West in the late fifties. “Barbarian” is an allusion to the “barbarian stigma” of Communism that weighed so heavily on him when he found himself confronted with the culture of the free world. In Wróblewski’s work and artistic thought, a barbarian is someone who destroys the existing culture and mercilessly takes advantage of his superiority over others. He is an executioner whose superiority often consists solely in the fact that he is alive, and as such the artist considers him a metaphor of the Nazi occupation. Wróblewski’s brief journey through art was an oscillation between the worlds of the living and the dead, the perpetrators and the victims, disaster and subsequent reconstruction.

In 1945, following his repatriation from Vilnius, Wróblewski embarked on the study of painting and sculpture at the art academy in Kraków. In opposition to the Kapist current – a derivation of modern French art – which dominated at the school, he and others (including the later film director Andrzej Wajda) founded the Autodidactic Group. His paintings were first shown in public in 1948 at the 1st Exhibition of Modern Art in Kraków. He also studied art history at the university from 1945 to 1948 and produced numerous theoretical texts and ideological statements which were published in art magazines.

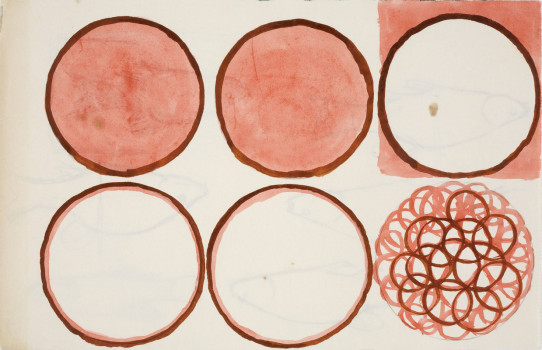

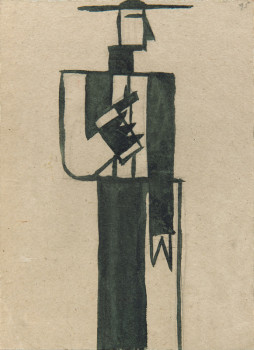

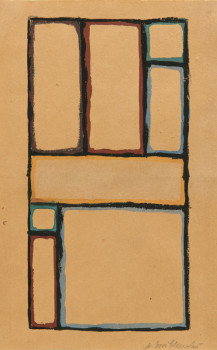

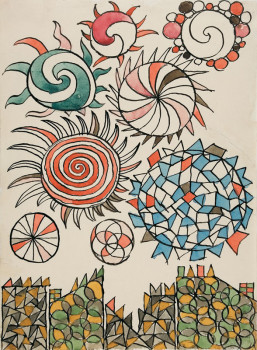

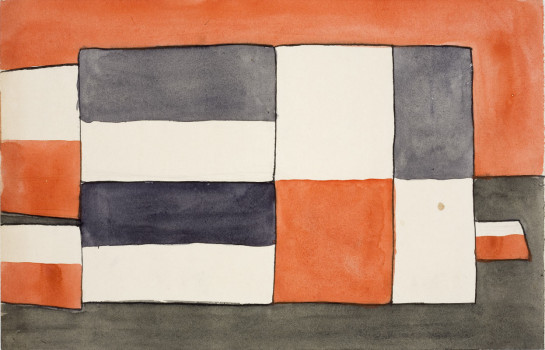

Wróblewski’s work of the late forties is an endeavour to come to terms with the catastrophism of post-World-War-II modernism. He thought of art as a means of constructing a new order and considered it closely connected to the idea of civilization’s progress. With compositions whose geometric or architectonic quality gives them an aura of modern functionality, he attempted to describe the reality of a utopia. He used abstract art to depict cosmogonies and other creation processes. Constructed of elementary forms, the paintings’ subtle architecture is informed by a strangely inspirited dynamic. In a gouache such as Sky Above a Town of 1948, for example, the mosaic-like celestial bodies feed on a kind of constant motion to produce an energy that gives expression to the relationship between the empty but animated space and the closed blocks of the human world. Precisely in works such as these, the idea crystallizes of the painting as an autonomous whole based on contrasts. In the Sunken Cities series, the geometric abstraction thus energized merges with a dream world. One by one, fish stream into a universal city just in the process of emerging or re-emerging. In Judeo-Christian tradition, the city submerged in a deluge is the prototype of a future civilization which at the same time has its point of departure in a mythical, biblical age.

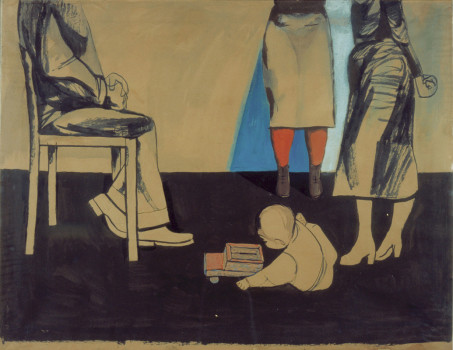

Whereas Wróblewski’s abstract paintings lend expression to cosmogonies, his figurative works allude to physical and emotional distress and deconstruction. Particularly in the well-known Executions series, the dramaturgy bears resemblance to the photojournalistic feature. The artist’s foremost aim in his treatment of this type of theme was a communicative style of painting that would be comprehensible to one and all. He wanted to bring about a “mobilization of feelings” and formulated the following radical intent: “I want a painting to have an unequivocal impact; I want it to evoke in the beholder precisely the experience I envisioned – and in every beholder the same experience.” Disappointed by the doctrine of Social Realism he had propagated for a time, he turned away from it with his paintings of 1956–57, only to be labelled a “neo-barbarian” by his social and cultural environment.

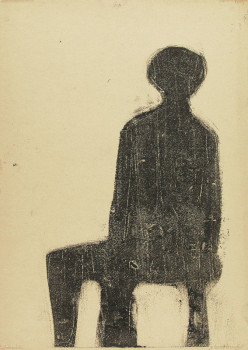

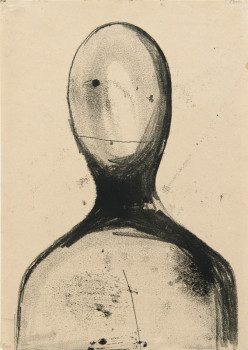

On the basis of war experiences in his private sphere and as a witness to Poland’s biological, material and cultural destruction, the artist was no stranger to the idea of civilization’s general demise. Reality seemed to have mocked the twentieth century’s utopian dreams and ideals. In his later works, however, he linked the universal catastrophe with the individual and the body. Corporality as Wróblewski depicted it has a dual quality: it is fragile, and can be attacked and destroyed, and at the same time it entirely determines human existence. The artist undertook numerous attempts to investigate the body’s resilience in his works, for example by robbing it of its head, exposing it to extreme light, reducing it to pure functionality or de-individualizing it.

Andrzey Wróblewski is today considered one of the most important artists of post-1945 Central and Eastern Europe. In Poland he exerted a decisive influence on the development of a new figurative style in the sixties as well as the “Young Painting” of the eighties. In 1958 and 1997, the Zacheta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw organized major retrospectives of his work, as did the National Museum in Kraków in 1998. In 2010, the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven staged a show entitled To the Margin and Back introducing his oeuvre to an international public for the first time. A comprehensive exhibition of his work is scheduled to take place at the K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen in Düsseldorf in 2013.

Katarzyna Falecka, Berlin 2011