Gallery exhibition

Eberhard Havekost, Markus Döbeli, Tatjana Doll

Schweigen

more about

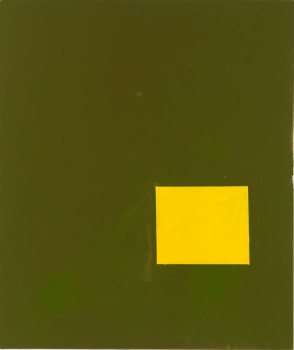

Eberhard Havekost Secrets (of Success) 3/4 (Forever Unfinished), B10; 2010

Oil on canvas; 30 x 50 cmm

Eberhard Havekost

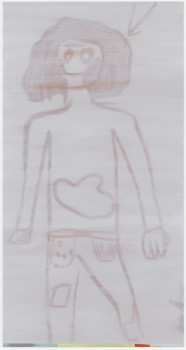

Eberhard Havekost’s painting makes reference to the world of everyday imagery. Technical reproductions, and often his own digital photographs, serve him as models or guides for his oil paintings. One element that links the primarily dark paintings on view in the exhibition is the fact that the artist shows very flat objects, or their flattest sides, or presents the motifs in such a way as to emphasize their surfaces. A poster, a child’s drawing on a sheet of paper, two black leather armchairs, a dirty window pane. The painter’s concentration on the process of pictorialization and the erratic conditions of sensory perception are discernible in the strategic transformation from flat (original object) to flat (technically produced reproduction) to flat (manually executed painting). He further emphasizes this process by frequently examining the same object in several divergent paintings. As the viewer’s desire for access to the subject grows, the absolute availability of the electronic image collides with the inadequacy of the objects depicted on the surfaces of these works.

In every process of image generation, breaks and gaps can come about that disturb the enlightened analytical demand for completeness – whether in the human being’s “dematerialized”, subjective gaze at his tangible surroundings, or in the respective moment in which a reproduction is connected to a surface and physically materializes. In the case of a painter seeking to take measures against the dematerialization of visual perception, it is precisely where the concern is with breaks and gaps that his interest seems to condense.

Whereas Tatjana Doll and Markus Döbeli are both represented in the show with works of very large dimensions, Havekost shows multipartite works. He thus emphasizes the connection of each one of his paintings to a system. Katy Siegel regards it as a tremendous strength that Havekost does not organize but rather multiplies. The constantly changing fundamental affinities between things and pictures, between experience and painting, can thus be demonstrated. His more recent paintings “test the possibility of moving away from the familiar oppositional categories – photography and experience, mine and yours, subject and object – to find the moments of interaction between them that deserve their own name, their own paintings.” Moments of interaction between a systematically selected photographic model, an instinctive spatial construction and the two-dimensional surface of the picture, between the precarious encounter of surface and paint, between myself (the seeing subject) and the object (a painting) I am out to conquer analytically, between my own physicality and that of the painting. Havekosts’s works push themselves somewhere into the space between these complicated approximation endeavours. As an enhancement to those of his paintings he refers to as “reproductive”, the “realistic” paintings (or “material conception paintings”) maintain an independent physicality and presence of their own. In the four-part ensemble Secrets (of Success) 1/4–4/4, it is the small work Forever Unfinished. Here the artist transferred the paints from the palette to the canvas with crude brushstrokes, while or after he worked on the other three paintings. Perhaps it points pars pro toto to a specific moment during the many individual steps of painterly pictorial production, captures it, freezes it, zooms in on it. Or it emphasizes moments of chance or arbitrariness, moments and things that exist independently of our perception, and, as we watch, takes a self-confident stance against methodical painting and the attributions that automatically come to our minds.

Markus Döbeli

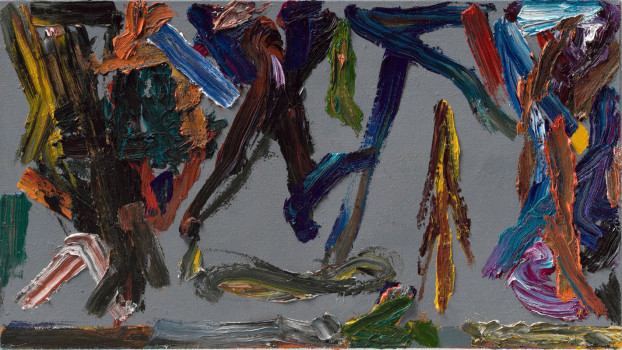

From Havekost’s pensive dark material gravity, Markus Döbeli lures us into bright spaces of light and colour. Döbeli has been working on his oeuvre – which is characterized by extreme formal coherence, unprogrammatic unworldliness, and exceptionally rigorous consistency – for more than twenty years. His distinctive abstractions etch themselves in our memories not least of all because of their inherent contradictions. The investigation of the material circumstances of painting contrasts with immersion in colour gradients that appear to float. The intimate effect resulting from the works’ unmistakable affinity to watercolour painting is difficult to reconcile with their spatial dimensions. It is precisely in this aspect that we can pinpoint what makes Döbeli’s work remarkable: he conquers the canvas with the formal vocabulary of watercolour – a medium he has mastered for many years.

Despite their sometimes tremendous size, Döbeli consistently chooses his formats in such a way that the painting can be visually comprehended by the beholder in its entirety. And what presents itself to my gaze there: floods of colour, consisting of highly diluted, glazed acrylic, gush across the surface. Mountain, ocean or jungle landscapes without contours emerge. Contours can be perceived only in the occasional cases in which the painter cuts up the canvas. Sometimes a reverberation of the painterly gesture can still be sensed; sometimes the veils of colour breathe into one another with apparent complete weightlessness; superimposed layers of clouds in shades of yellow, red, blue and green converge in beguiling, almost erotic instances, only then to detach themselves from one another again elsewhere.

Concentrating on such virtually ephemeral instances, the purity of this painting possesses a quality of freedom and openness that transcends all gimmickry. I find myself almost being afraid that the thin, diaphanous paint will evaporate. Such sensations gain in intensity when we take into account that acrylic releases oxygen through evaporation during the drying process (whereas oil and industrial paint, the materials Havekost and Doll work with, absorb oxygen). “In front of Markus Döbeli’s paintings, one literally spells backwards – not they are the unreal behind a real world of signs, images and meanings. On the contrary, they represent the physically experienceable reality that is constantly buried beneath the illusory images of everyday life.”

Tatjana Doll

Tatjana Doll is interested in precisely those illusory images of everyday life, though she would probably refer to them as “lies of memory”. As is the case with the majority of Havekost’s works, her point of departure is also always a technically reproduced image. Objects from the everyday urban world, pictograms or reproductions of artworks, banal articles of daily use or images charged with art or cultural historical meaning – she carefully chooses from the physically passive image archive that constantly surrounds us, but is not at our command. These images serve her as a projection surface for an artistic inquiry directed not at the motif but at its impact. During a painterly process between construction and deconstruction, a shift occurs. The result is a spirited and authentic painterly invention which in turn inquires into its own potential for impact.

Doll’s chief concerns are neither with socio-critical nor with media-critical approaches – nor does she aim for a return to a possible, primeval veracity of artistic works or the continuation of a certain mode of reading them. On the contrary, she thinks about how “illusions” emerge, about how the passive image archive is constituted, and what effects it has on us. Such complex questions are raised in connection with the works whose titles include the prefix RIP – works related to examples from the history of art that have undergone wide photographic reproduction. How did these icons, as she calls them, find their way into our individual and collective pictorial memories; why do they literally brand themselves there to a degree sometimes brutal, and what life of their own can they develop there? What information, what content gets lost in the course of these processes, and what information and content are gained? These questions are especially interesting in the light of Doll’s “mechanized” painting manner, which also distinguishes her other motif categories. Tatjana Doll does not find fulfilment in reproduction, but reveals in her painting a “convincing concept for the constitution of the artistic subject”.

To single out one example, in her RIP_Venus of Willendorf Doll wrests surprising facets from Willem de Kooning’s scandalous Women of 1950–52 (a brutally abstract depiction of a buxom female figure with which he antagonized his critics partly because it represented a departure from a formal language that had been indebted to Abstract Expressionism), whether through the gaze of the woman at the gaze of a man at a woman (also: the gaze of the female painter at the gaze of the male painter at a model), or simply the subject’s new ferocious and powerfully colourful formal treatment. The industrial paints Doll has been working with for many years – toxic, artificial fluids that surround us constantly – play a fundamental role in the visualization of the subject through the targeted painterly annihilation of the original The black paint drips decisively down the vertically placed canvas, ruining the contours of the flower in PICT_Narcisse II. A destructive effect thus comes about: the painterly treatment seems to mock the guileless self-complacency of the flower’s existence.

There is something disconcerting about Tatjana Doll’s painting because it constantly vacillates between exploration of painting as such and exploration of the image she has chosen as a model. At the same time, however, it is a constant endeavour to take action against the dominance of the virtually impenetrable membrane of signs and images shrouding our conception of reality.

Schweigen

For this exhibition, the artists chose the eloquent title “Schweigen” – a concept that, in relation to their pictorial worlds, can be understood in manifold and contrary ways. As a vow or commandment, a right or obligation, the opposite of information or a special form of communication, or in the sense of intent alertness, alluring injunction, provocation, deliverance, denial, abstention. In our materialistic information age that places ever more at our disposal at an ever faster rate, the paintings on view are capable of holding their own because, with their silence, they spark a desire for something that evades that seemingly limitless availability.

Eberhard Havekost

Die Malerei von Eberhard Havekost bezieht sich auf die alltägliche Bilderwelt. Als Vorlage oder Anleitung für seine Ölgemälde dienen ihm technisch reproduzierte Abbildungen, oft auch eigene digitale Fotografien. Ein verbindendes Element der in der Ausstellung gezeigten, überwiegend dunklen Gemälde besteht darin, dass der Künstler sehr flache Gegenstände oder deren flachste Seite zeigt, bzw. die Motive so präsentiert, dass ihre Oberfläche betont wird: Ein Plakat, eine Kinderzeichnung auf einem Blatt Papier, zwei schwarze Ledersessel, eine verschmutzte Fensterscheibe. In der strategischen Umwandlung von flach (ursprüngliches Objekt) zu flach (technisch reproduzierte Abbildung) zu flach (manuell erzeugtes Gemälde) wird die Konzentration des Malers auf Prozesse der Verbildlichung und die wechselhaften Bedingungen sinnlicher Wahrnehmung erkennbar. Dies unterstreicht der Maler, indem er häufig denselben Gegenstand in mehreren, voneinander abweichenden Gemälden beleuchtet. Während mein Wunsch als Betrachter nach einem Zugang zum Dargestellten wächst, kollabieren in der Fläche seiner Gemälde die absolute Verfügbarkeit des elektronischen Bildes und die Unzulänglichkeit der Dinge.

In jedem Prozess der Bilderzeugung können Brüche und Lücken entstehen, die den analytischen, aufklärerischen Anspruch auf Vollständigkeit stören. Sei es im „entmaterialisierten“, subjektiven Blick eines Menschen auf seine dingliche Umgebung, oder dem jeweiligen Moment, wenn ein Abbild an einen Träger gebunden wird und sich physisch materialisiert. Gerade wenn es um Brüche und Lücken geht, scheint sich das Interesse des Malers zu verdichten, der mit seinen Bildern etwas gegen die Entmaterialisierung des Blickes unternehmen will.

Während Tatjana Doll und Markus Döbeli mit einigen sehr großen Formaten in der Ausstellung vertreten sind, zeigt Havekost also mehrteilige Arbeiten. Damit betont er den Systemanschluss, den jedes seiner Bilder hat. Katy Siegel sieht eine enorme Stärke darin, dass Havekost multipliziert und nicht organisiert. So können die stets wechselnden Wesensverwandtschaften zwischen Dingen und Bildern, Erfahrung und Malerei aufgezeigt werden. Seine neueren Gemälde „erproben die Möglichkeit einer Abkehr von vertrauten oppositionellen Kategorien – Fotografie und Erleben, mein und dein, Subjekt und Objekt –, um vielmehr Momente der Interaktion zwischen ihnen aufzuspüren, die ihren eigenen Namen, ihre eigenen Gemälde verdienen.“ Interaktionsmomente zwischen planvoll ausgewählter fotografischer Vorlage, unwillkürlicher Raumkonstruktion und der zweidimensionalen Bildoberfläche, zwischen dem prekären Aufeinandertreffen von Bildträger und Farbe, zwischen mir, dem sehenden Subjekt, das auf ein Objekt (ein Gemälde) trifft und es analytisch bezwingen will, zwischen meiner eigenen Körperlichkeit und derjenigen der Malerei. Havekosts Gemälde schieben sich irgendwo in den Raum zwischen diese komplizierten Annäherungsversuche. Ergänzend zu denjenigen Gemälden, die Havekost „reproduktiv“ nennt, behaupten die „realistischen“ Bilder (oder „Materialverständnisbilder“) eine eigene, unabhängige Körperlichkeit und Präsenz. Im vierteiligen Ensemble Secrets( of Success)1/4-4/4 ist dies die kleine Arbeit Forever Unfinished. Hier hat der Maler die Farben in groben Pinselstrichen von der Palette auf die Leinwand gebracht, während oder nachdem er an den drei anderen Gemälden arbeitete. Möglicherweise verweist es pars pro toto auf einen spezifischen Moment während der vielen einzelnen Schritte der malerischen Bilderzeugung, festgehalten, eingefroren und herangezoomt. Oder es betont Momente von Zufall oder Willkür, Momente und Dinge die unabhängig von unserer Wahrnehmung existieren, und stellt sich der planvolle methodischen Malerei und den Zuschreibungen während unserer Betrachtung selbstbewusst entgegen.

Markus Döbeli

Von der nachdenklichen, dunklen Materialschwere Havekosts entführt Markus Döbeli in strahlende Räume des Lichts und der Farben. Seit über zwanzig Jahren arbeitet Döbeli an einem in seiner Konsequenz außergewöhnlich stringenten Oeuvre, unprogrammatisch-weltabgewandt und formal äußerst schlüssig. Seine unverwechselbaren Abstraktionen bohren sich nicht zuletzt aufgrund ihrer immanenten Widersprüche ins Gedächtnis: Die Erforschung der materiellen Gegebenheiten der Malerei steht der Versenkung in scheinbar schwebende Farbverläufe gegenüber. Die intime Wirkung, die sich aus der unübersehbaren Verwandtschaft zur Aquarellmalerei ergibt, ist schwer mit den räumlichen Dimensionen dieser Malerei in Einklang zu bringen. Gerade hierin liegt das Bemerkenswerte an Döbelis Arbeit: Mit dem Formenvokabular des Aquarells, einem Medium, das er schon seit Jahren beherrscht, erobert er die Leinwand. Trotz ihrer zum Teil enormen Größe sind Döbelis Formate immer so gewählt, dass sie vollständig vom Betrachter erfasst werden können. Und was bietet sich meinem Blick dort: Auf transparenten Leinwänden ergießen sich Farbfluten von stark verdünntem, lasierendem Acryl. Es erwachsen konturlose Gebirgs-, Meeres- oder Dschungellandschaften. Nur dann, wenn der Maler gelegentlich die Leinwand zerschneidet, lassen sich Konturen nachvollziehen. Manchmal noch ist ein Widerhall der malerischen Geste zu erahnen, manchmal hauchen die Farbschleier scheinbar völlig schwerelos ineinander; sich überlagernde Wolken in Schattierungen von Gelb, Rot, Blau und Grün berühren sich in betörenden, fast erotischen Momenten, um sich an anderer Stelle wieder voneinander zu lösen.

Auf solche gleichsam ephemeren Momente konzentriert, liegt in der Reinheit dieser Malerei etwas sehr Freies und Offenes, das gegenüber jeder Effekthascherei erhaben ist. Fast habe ich Angst, dass sich der dünne, durchlässige Farbauftrag gänzlich verflüchtigt. Solche Empfindungen gewinnen an Dimension, wenn man den Umstand berücksichtigt, dass Acrylfarbe während des Trocknens durch Verdunstung noch Sauerstoff abgibt (wohingegen Öl und Lack, womit Havekost bzw. Doll arbeiten, Sauerstoff aufnehmen). „Vor Markus Döbelis Bildern buchstabiert man gleichsam zurück: Nicht sie sind das Unwirkliche hinter einer realen Welt der Zeichen, Bilder und Bedeutungen. Vielmehr repräsentieren sie eine physisch erfahrbare Realität, die durch die Trugbilder des Alltags permanent verschüttet wird.“

Tatjana Doll

An solchen Trugbildern des Alltags ist Tatjana Doll interessiert, wobei sie vermutlich eher von „Lügen des Gedächtnisses“ sprechen würde. Wie für die meisten Arbeiten von Havekost ist auch ihr Ausgangspunkt eine technisch reproduzierte Abbildung. Objekte aus der urbanen Lebenswelt, Piktogramme oder Reproduktionen von Kunstwerken; ob banaler Gebrauchsgegenstand oder kunst- und kulturhistorisch Aufgeladenes – sorgfältig wählt sie aus dem körperlich passiven Bildarchiv aus, das uns täglich umgibt, über das wir aber nicht verfügen können. Diese Bilder dienen ihr als Projektionsfläche für eine künstlerische Auseinandersetzung, die nicht dem Motiv, sondern dessen Wirkung gilt: Während eines malerischen Prozesses zwischen Konstruktion und Dekonstruktion findet eine Verschiebung statt. Das Resultat ist eine vitale und authentische malerische Erfindung, die wiederum selbst ihr eigenes Wirkungspotential befragt.

Dolls primäre Anliegen verfolgen weder gesellschafts- noch medienkritische Ansätze – auch nicht eine Rückbesinnung auf eine mögliche, ursprüngliche Wahrhaftigkeit künstlerischer Werke oder die Fortführung einer bestimmten Lesart. Vielmehr denkt sie darüber nach, wie „Trugbilder“ entstehen, auf welche Weise sich das passive Bildarchiv konstituiert, und welche Auswirkungen es auf uns hat. In Bezug auf die mit dem Präfix RIP- betitelten Arbeiten, welche sich auf Werke der Kunstgeschichte beziehen, die eine breite fotografische Vervielfältigung erfahren haben, werden so komplexe Fragen aufgeworfen. Wie sind diese Ikonen, wie sie sie nennt, in unser individuelles und kollektives Bildgedächtnis geraten, warum brennen sie sich dort stellenweise brutal ein, und welches Eigenleben können sie dort entwickeln? Welche Informationen, welcher Gehalt gehen im Verlauf dieser Vorgänge verloren, welche kommen hinzu? Dies wird besonders interessant im Lichte von Dolls „mechanisierter“ Malweise, die auch ihre anderen Motivkategorien kennzeichnet. Tatjana Doll geht nicht im Reproduktiven auf, sondern lässt in ihrer Malerei ein „überzeugendes Konzept für die Konstitution des künstlerischen Subjekts“ erkennbar werden.

Willem de Koonings Skandalbild Woman I von 1950-52 etwa, mit dessen brutal-abstrahierender Darstellung einer drallen weiblichen Gestalt er seine Kritiker auch deswegen gegen sich aufbrachte, weil er sich von einer bis dato dem Abstrakten Expressionismus verhafteten Formensprache abgewandt hatte, ringt Doll mit RIP_Venus of Willendorf überraschende Facetten ab: Sei es durch den Blick der Frau auf den Blick eines Mannes auf eine Frau (auch: der Blick der Malerin auf den Blick des Malers auf ein Modell), oder schlicht die farbgewaltig-furiose formale Neubehandlung. Elementaren Anteil an der Vergegenwärtigung des Dargestellten durch die gezielte malerische Zerstörung der Vorlage haben die Industrielackfarben, mit welchen Doll seit Jahren arbeitet; giftige, künstliche Flüssigkeiten, die uns täglich umgeben. Entschlossen läuft die schwarze Farbe die aufgestellte Leinwand herunter, und zersetzt die Konturen der Blume in PICT_Narcisse II. So entfaltet sich eine vernichtende Wirkung: Die malerische Behandlung scheint der arglosen Selbstzufriedenheit ihrer Existenz zu spotten.

Tatjana Dolls Malerei wirkt verunsichernd, da sie permanent zwischen der Auseinandersetzung mit Malerei an sich und der Auseinandersetzung mit der Vorlage oszilliert. Immer jedoch scheinen ihre Gemälde bestrebt, durch eine subjektive, malerische Divergenz vehement gegen die Herrschaft der Zeichen- und Bildermembran vorzugehen, die sich schwer durchdringbar um unser Wirklichkeitsverständnis legt.

Schweigen

Die Künstler haben der Ausstellung den beredten Titel „Schweigen“ gegeben, der in Bezug auf ihre Bildwelten in vielfältige und oppositionelle Richtungen gedacht werden kann. Gelöbnis oder Gebot, Recht oder Pflicht, als Gegenteil von Information, oder als eine besondere Form von Kommunikation, im Sinne angespannter Aufmerksamkeit, einladender Aufforderung, Provokation, Erlösung, Verweigerung, Enthaltung. Die gezeigte Malerei kann sich auch deswegen im materialistischen Informationszeitalter behaupten, in dem immer mehr, immer schneller verfügbar gemacht wird, weil sie durch ihr Schweigen ein Begehren weckt nach etwas, das sich dieser scheinbar grenzenlosen Verfügbarkeit entzieht.