Gallery exhibition

more about

Born in 1979 the artist studied at the University of the Arts (Universität der Künste) in Berlin from 2001 to 2008 under Christiane Möbus. He lives and works in Berlin, where, amongst other things, in 2007 he co-founded the art initiative TÄT, a showroom in Schönhauser Allee 161a, which is run as a display gallery by graduates from his former univeristy, the UdK. One of the better and more exciting project spaces in this city, which is an ever increasing maze for art lovers.

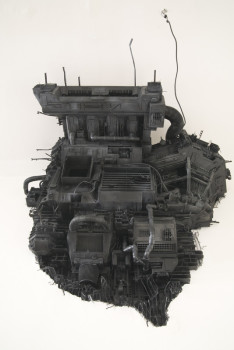

Philip Topolovacs’ first large personal exhibition includes a large, multipart polyester form taken from a sandheap which he had made in a sandpit in Brandenburg. From from this piece alone, the profound, humourous outlook on the world, already announced in the title, is apparent. Alongside this there is an enlargement of an old relay switch. These pieces were, and are, used, to switch high voltage in industrial equipment. The promise of functionality, of transmission of energy, release and generation thus constitutes the fascination of the technological and its aesthetic appeal. When transferred into the gallery, the functional aesthetic is, for all intents and purposes, reversed, twisted and turned into a self-contained sculptural object. As if that wasn’t enough, there is a circuit diagram of Johann Philipp Wagner’s electromagnetic hammer on the wall. One of the most fundamental electronic circuits, from the early period of electromechanics. This simplicity with the monstrous name (you can almost hear the connectors of the 30 000 volt equipment cracking) is captured with nearly classic champion technique, enlarged as a wall drawing. Think of the new experiment just beginning now in the nuclear research centre Cern, which may give us more insight into the big bang theory and black holes, it is here that the antipole is set. The electromechanic base elements elevate (similar to the objects of Arte Povera) the view to the functional framework beyond the pleasant appearance, even if that may irritate the observer and the aesthetic sensibilities. In his work Topolovac is concerned with the question of image and reality, formats and magnitudes of the aesthetic. Is the image of a sandheap more than its potential model? We believe we can already say. If it comes as such a chipped object, we don’t just play in the sand there anymore, rather we think of the wonders of Brandenburg, of Friedrich’s dream, of Lessing’ s cry and are almost immediately Kafka’s Gregor Samsa. Solid is not meant firmly enough, it could even refer to coagulated slime, the form outlines are screwed together with machine bolts and then what’s inside, beneath it? Philip Topolovacs works are thereby necessarily to be understood poetically: materially alluring and at the same time simple but looking further into the black-romantic. If you go through the gallery, you’ll come across a burn in the wall. On the other side weird technical installations loom far into the room, which have hidden themselves behind the slick trappings of the built in wall. Who has played with fire here and what type of construction was it? The technological mycelium of the requirements of everyday existence is connected to processes and structures, power plants and manufacturing plants, which seem all too far away when we’re standing in the supermarket or watching the television, but which arouse horror when we become aware of them or when we come into direct contact with them.

The eerie, gross extent of refining, mass processing and container harbours give rise to a fear of the effects of the human influence and to the desire to distance oneself from the system, or, as the case may be, from aspects of the system. The idea of terrorist attacks as a reason for destructive interference in systems of a technical as well as a social nature, is close to our hearts these days. The fall of the Twin Towers into an enormous, rising white cloud was also an aesthetic memorial to drywall construction methods. Emblematic pictures of destruction have accompanied the development of our engineered society for centuries. The mushroom cloud, the vapour trail of the falling space shuttle Challenger, the catastrophe of Ramstein. If we think of the cult film Blade Runner, Topolovacs’ installations could be read as a sign of our burnt out future. Here we see the artistic treatment of the breaking point of a technical civilisation, which becomes a wound. There is no progress without disaster, behind the smooth surface the ugly skeleton lurks. We could nearly talk of a vanitas sculpture according to Gaussian distribution; sparks will always fly, that’s what mathematics tells us, and the resut is system damage. But there is a comfort in this exhibition and it lies, as with every true Romantic, in the representation of the landscape. Only the landscape in Topolovac’s works dispenses with the real and presents a minitrurised mirage to the contrary. In numerous photos, the artist has captrued sandheaps and excavations in urban surroundings and thereby implies mountain landscape. The mountain motif is an artistic motif for longing from the 19th century. No German Romantic would be conceivable without a yearning glance out onto the mountain range. In the series “Mountains”, which represents the projection of an ever advancing model of longing, the artisitc strategy followed is of subliminating trivia in the copying and simultaneously of satirising its transfiguration. This is where, both in contrast and co-operation of the threatening elements, the exhibition finds its catharsis. You see what you think and you think what you believe you know. But that would only be simple logic. Philip Topolovac stops it there with the dialectic logic, don’t believe what you see and above all don’t think, great things could also not be found in the smaller details.